USEPA’s National Primary Drinking Water Regulation is final. Here’s how utilities can achieve compliance.

On April 10, 2024, United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) announced the final rule for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a part the National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR), establishing legally enforceable limits for six PFAS in drinking water. The regulation sets Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for PFOA and PFOS at 4.0 parts per trillion (ppt), and MCLs for PFHxS, PFNA, and HFPO-DA (or GenX chemicals) at 10 ppt. In addition to these individual MCLs, public water systems will be required to calculate a Hazard Index (HI) using the following formula if two or more of the four HI compounds are detected at the point of compliance.

An HI value of greater than 1.0 triggers a violation of the standard.

The final PFAS rule was published in the Federal Register on April 26, 2024, and is considered effective on June 25, 2024. Water utilities have three years, until April 26, 2027, to complete initial monitoring for these specified PFAS, and until the public must be notified of PFAS levels in their drinking water. If monitoring reveals PFAS levels above the promulgated standard in the drinking water at the points of entry into the distribution system, utilities have until April 26, 2029, or five years from promulgation, to implement solutions necessary for reducing these PFAS and complying with set MCLs and the HI. Ongoing compliance monitoring is required after the initial monitoring is completed.

That’s a brief summary of the final rule. And now that it’s here, what is the optimal course of action water utilities should take to achieve compliance?

In this Q&A, Garver Water Practice Leader Zaid Chowdhury, PhD, PE, BCEE, and author of the American Water Works Association’s Activated Carbon: Solutions for Improving Water Quality, discusses key aspects of the rule and provides a step-by-step plan for utilities to achieve compliance within the required timeframe.

Now that NPDWR is final, what is the central takeaway for water utilities?

Unless there is a court challenge, NPDWR will be implemented but water utilities will have a longer timeline than usual to comply. However, that longer timeline - five years - comes with a catch: after three years, utilities must notify the public of the concentrations of regulated compounds in their drinking water.

This seems to me a clear incentive for utilities to comply within a three-year timeframe. Otherwise, the utility is faced with the prospect of their annual consumer confidence report (CCR) informing customers that the water they have been drinking has a higher concentration of PFAS than USEPA mandates. So, one of the biggest takeaways for utilities is that it’s in your best interest to comply within three years.

That said, the five-year timeline does give utilities some leeway with regard to any potential slowdown from supply chain issues or other challenges that come along in the course of implementing a new treatment system.

What steps should water utilities take to achieve compliance with MCLs within the three-year time limit?

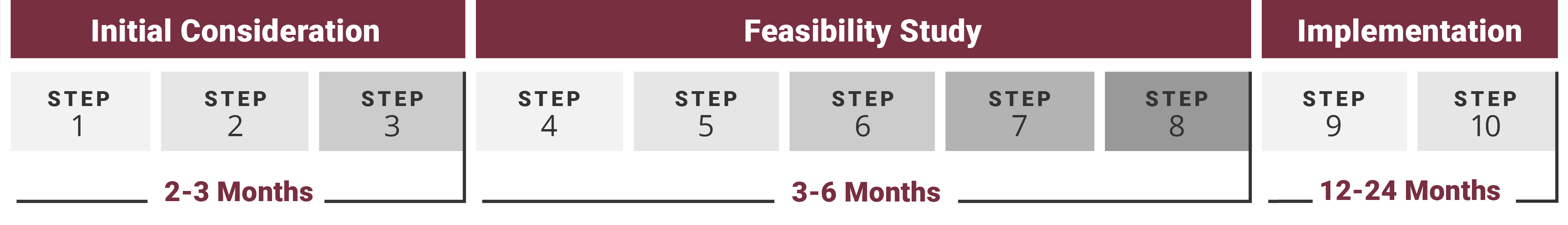

For all utilities, a good, general first move is to just get started, don’t delay. As for how to get started, I’ve created a roadmap to compliance that’s broken into a 3-Phase timeline and 10 practical steps. Each utility’s situation is different - some may only need to take steps one through three, others may need to take all 10.

Phase 1: Initial Consideration, 2-3 months

If they have it available, utilities can rely on the data they’ve been collecting under UCMR 5 along with any additional data to begin an assessment, with the goal of fully understanding their source water quality and current system. They should identify alternative water source options and begin to determine available space for treatment, should it be needed.

A utility’s water quality goal could be to comply with the regulation, or it could go further and be to remove the regulated contaminants to below detectable levels. Using knowledge of their customer base, water utilities should be able to adopt a water quality goal that matches their needs. Once the goal is set, utilities can determine if it can be met with or without treatment.

NPDWR has points of flexibility built in, and one of them is that utilities may choose to close contaminated wells or sources and seek new, uncontaminated drinking water sources. For some systems, such as groundwater systems with multiple wells, it may be possible to avoid treatment by no longer using any contaminated source or by adjusting blending ratios of sources to reduce the concentration of contaminants.

Utilities should assess existing treatment processes, evaluating their capabilities. Can they remove PFAS or improve PFAS removal with some adjustment? What minor modifications to the treatment process could be made to achieve additional removal? For example, at a water treatment plant with a current powdered activated carbon (PAC) feed system, it may be possible to improve PFAS removal by making minor adjustments to the PAC dose or mixing time at the plant.

If utilities go through this step and determine that no simple fix is available, they begin the more difficult task of proceeding to Phases 2 and 3.

Phase 2: Feasibility Study, 3-6 months

Next, utilities should determine if their water quality goal (set in step 2) could be achieved by treating only a portion of the water (side-stream) or if full-flow treatment is required. If the water quality goal is to comply with regulations only and the source water concentrations are not too high, side-stream treatment could be adequate; however, if the water quality goal is to reduce levels to below detectable values a full-flow treatment will most likely be required.

The NPDWR does not dictate which treatment technology water systems should use, instead giving them their choice of proven treatment options: granular activated carbon (GAC), anion exchange (AIX), reverse osmosis (RO), or nanofiltration (NF). Utilities may also consider innovative technologies, such as Fluoro-sorb®, or pursue technologies that destroy PFAS.

Since some available technologies may not fit on the site, it’s best to first create a conceptual layout of applicable processes on the existing treatment site and to assess each treatment approach, keeping a complete list of advantages and disadvantages.

For each evaluated treatment alternative, develop planning level cost estimates that adjust for local factors and supply chain issues. To help create high-level cost estimates, utilities can begin with USEPA’s spreadsheet-based cost models, or they can obtain preliminary technology costs from vendors.

After suitable technologies have been identified and evaluated and cost estimates have been prepared, it’s time for the engineer and owner to collaboratively examine and discuss this information. Appropriate weighting factors should be used to score each alternative, and each should be thoroughly vetted.

Initial design criteria for the selected technology can be found in previous publications from USEPA, AWWA, and similar journals. However, it’s best to obtain site-specific design criteria as selection of proper design criteria is the determining factor for effective technology performance and reliable operation.

The optimal approach to developing reliable design criteria is to conduct pilot-scale evaluation with the exact water that the technology will be required to treat. Bench-scale testing can also be performed to obtain reasonable design criteria. The utility’s consultant could perform these tests by themselves or in association with an academic institute.

Phase 3: Implementation, 12-24 months

Utilities may not have to fund PFAS treatment implementation using their own money or through immediate rate adjustments. Various loans and grants are available to help utilities fund these capital programs. Utilities should explore state revolving funds (SRF), direct federal funding from various agencies, and co-funding through Bureau of Reclamation and legacy PFAS chemical manufacturers.

In fact, utilities may begin exploring funding options earlier, in Phases 1 and 2, as there are federal and state programs that can provide funding for these earlier steps. This will depend on how their state implements funding provided by SRF, and whether or not the state has created grant and loan funding to go along with state funding to address PFAS.

A water utility typically works with an engineering company to complete preliminary and detailed design, refining cost estimates with the progress of the design and considering alternative procurement approaches. In some cases, pilot testing may proceed in parallel for a portion of the design project. In this instance, the design process should have some flexibility to accommodate pilot-testing findings.

With the help of a good consultant, a water utility could comfortably complete all three phases of activities within a three-year period. If the pilot testing in Phase 2 extends beyond the six-month period, a utility may still proceed with Phase 3 in parallel using the initial results of pilot testing. The results of pilot testing could be incorporated into the design at a later stage.

What obstacles or challenges to compliance should utilities be aware of?

Time is of the essence, given the requirement for public reporting of PFAS levels in 2027, and so the chief obstacle utilities should look out for is supply chain delay for necessary equipment and materials procurement. For some equipment (e.g., large electrical equipment), the lead time is 40 weeks — nearly a year.

Utilities must be aware of and monitor supply chain issues and expedite the first steps in the compliance process by pre-ordering critically needed materials and equipment as much as possible.

Beyond the 10 steps you’ve outlined, are there any other proactive measures utilities should take as they seek to comply with NPDWR?

Since USEPA gives primacy to state regulatory bodies, those state regulators are in charge of implementing the regulation. It is possible that they could make the regulation more stringent or make changes to how to comply or calculate MCLs. It’s hard to imagine that states would seek to make NPDWR stricter, but it is possible.

Utilities can take the proactive step of getting in touch with state regulators and finding out exactly how they plan to implement the rule. Being in contact with regulators can also help keep utilities aware of any potential lawsuits that might delay or lead to changes in the rule.

Another proactive step is to use industry resources as much as possible. AWWA publishes regular updates and welcomes participation from utility members in groups and on committees, for example. Attending any stakeholder meetings, webinars, seminars, or conferences is another way for utilities to stay on top of any news about NPDWR.

How can Garver help?

We provide comprehensive PFAS services, including sampling and analysis of data, feasibility studies and treatment process desktop evaluations and piloting, treatment process design, cost estimation, funding procurement, and more.

Contact me or visit our website to learn more about our PFAS services, our experience successfully providing proven treatment solutions and our industry-leading expertise, and start tackling the challenges of PFAS.

Share this article